Are you missing vulnerable children because of ‘bad’ data?

Please excuse the analogy of comparing potentially vulnerable children with WW2 fighter planes but please bear with me whilst I illustrate an important point.

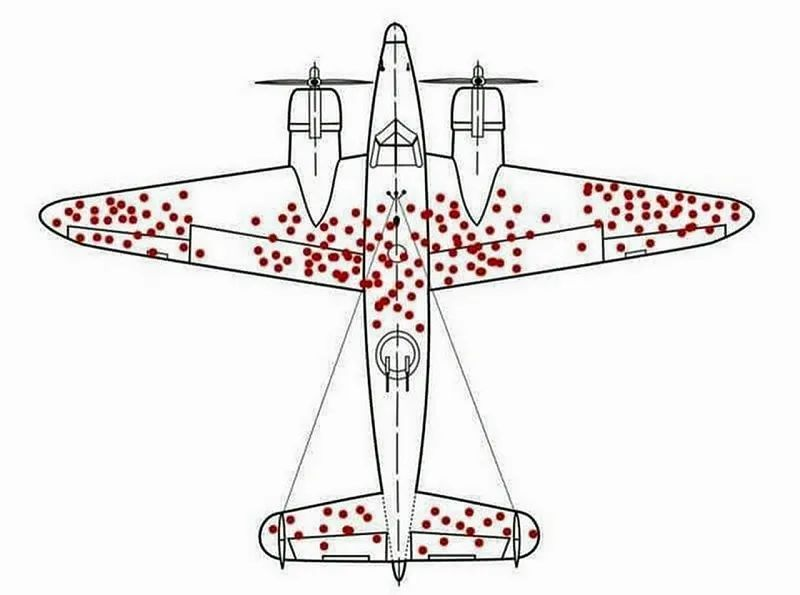

During air raids over occupied territory during WW2 brave pilots and aircrew risked their lives. Not all of the planes returned. Some of the planes that did return were damaged by shrapnel and bullet holes.

The Allied Forces leaders were keen to improve the survival rate of the planes and their crew. They, therefore, instructed scientists to analyse and map the areas on the plane that were most damaged. After careful analysis, it was decided to strengthen these areas with thicker armour to improve the planes’ survivability.

Several air raids later, it was noticed that this was having no impact on survival rates whatsoever. The Allied leaders were baffled.

A mathematician, Abraham Wald, pointed out that perhaps the reason certain areas of the planes weren’t covered in bullet holes was that planes that were shot in certain critical areas did not return. This insight led to the armour being reinforced on the parts of returning planes where there were no bullet holes.

The vital ‘data’ that was missing was where the bullet holes were on the planes that did not return. These areas of damage would tell engineers where to reinforce the planes.

Too often in education, we are trying our best to improve provision for children based on equally ‘bad’ or ‘missing’ data.

Take measuring mental health and well-being in young people. The very individuals you are trying to identify and support are likely to be the ones who, for whatever reason, do not wish to reveal their true feelings. A pupil voice questionnaire can be easily navigated by a young person who does not want to reveal how they are feeling. Or indeed, a young person does not know how to interpret their emotions or their mental state and is unable to articulate this onto paper. Some young people may have no awareness that they are on a downward trajectory in terms of mental health and well-being.

As an ex-inspector and ex-Headteacher, I have known a questionnaire to ask if a child “feels safe in school?” The answer allows only ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ Again, the issue here is threefold: Firstly, the definition of ‘safe’ to one child can be very different from that of another child. It could relate to a single incident that has occurred in the very recent past or a pattern of events consistent over time. Both qualify as ‘yes.’ Secondly, children vary in their ability to measure how ‘safe’ they are. My children would comfortably stand on the very edge of a cliff during a family walk in the countryside without any thought that they might not be safe. And thirdly, and critically, some children will not want to share how ‘safe,’ or not, they may feel.

These are what we call the ‘hidden middle’ – the non-returning planes if you like.

At STEER Education we have developed an innovative early identification assessment tool that can measure quantitatively every pupil’s social-emotional risk factors. This sophisticated tool is not a simple questionnaire with its associated limitations. It does not rely on the pupil’s directly expressed voice as a questionnaire might. It does not rely solely on a subjective expressed view of a teacher.

In all my schools, I introduced a proactive wellbeing early identification toolkit called STEER Tracking which I asked all the pupils to undertake. It involved imagining and visioning a pleasant ‘Space’ and then asking a series of questions about it – “Would you share your Space? Would you share your feelings with others in your Space?” etc. The young people found it “weird, Sir!” but the answers given allowed me to get a measure of a child’s ability to self-regulate. Their ability to “STEER” the road of life. It was a game changer in terms of pastoral care and by extrapolation academic progress, behaviour and attendance.

Because pupils are not asked direct questions, but value neutral questions which elicit unconscious biases in their thinking, it’s less easy for them to see what is the ‘right’ answer, and what would cause concern. For E.g. ‘’Do you like exploring new parts of your Space?’’ STEER Tracking measures, amongst other risk factors, a pupil’s Self Disclosure bias, indicating how likely they are to share what they really think and feel in school. If pupils tried to ‘game’ the assessment, their data would be flagged. STEER Tracking reports a child’s hidden voice.

At last, a tool that does not miss vital data or even worse gives you ‘bad’ data. No planes, or indeed children, are missed.