What the data shows: How young people’s wellbeing will be affected by the latest Covid restrictions

The latest government Covid measures imposed on schools are designed to suppress the spread of Covid whilst keeping schools open. What impact are they likely to have on young people’s wellbeing?

Article key points:

– Closing schools seriously dysregulates young people’s social-emotional wellbeing. The government is right to prioritise keeping schools open.

– Wellbeing recovery from school lockdowns is taking students a long time. Latest data suggests that, on a key measure, risks are still 25% higher than at the start of the pandemic.

– Even minor Covid measures which reduce students’ predictable routines, face to face interactions or create a barrier between them and teachers, will have a further negative wellbeing impact.

CURRENTLY, the new government restrictions for schools are limited to student mask wearing at all times during the school day. However, even if schools remain open, regulations around self-isolation, coupled with the very high transmission of Omicron, make it highly likely that schools will face teaching disruptions in the coming weeks. Staff resources are unlikely to be flexible enough to absorb these impacts without some impacts on face to face teaching.

In addition, a proportion of young people will themselves be isolating due to Covid. Learning will be back to online in such cases at best. The hope is that whole classes or year groups will not be sent home.

In the face of this disruption, is there any data to indicate what the likely impact will be on young peoples’ mental health and wellbeing?

Data of the impact from previous measures tracks a clear wellbeing trajectory

STEER has tracked a measure of UK young peoples’ mental health and wellbeing since 2016 and continued to do so during the pandemic. You can read about our methods, data samples and analysis here. As one of the only UK organisations to have pre-pandemic in-school wellbeing tracking data, our data provides an important objective story of the pandemic impacts on the ability of young people to self-regulate.

Self-regulation is the capability a young person has to navigate the social-emotional road ahead of them: For example, to make wise choices in terms of social risk-taking; to overcome personal or academic set backs; to establish healthy relationships and to develop emotional self-strategies that are protective factors for good mental health.

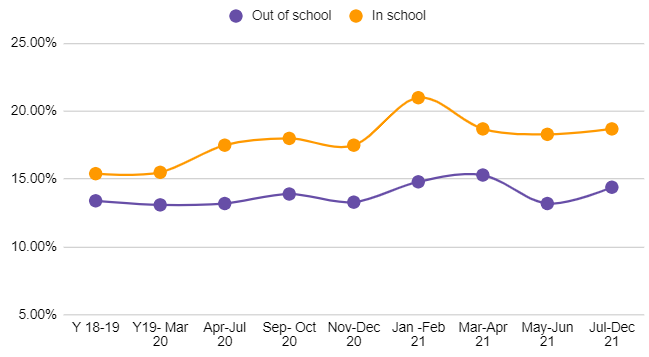

The graph below shows how the Covid-protective policies imposed on schools during the pandemic (remote teaching, lockdowns, masks etc) have changed the road for young people and affected their ability to self-regulate.

The Y axis shows the percentage of 11-18 year olds with poor self-regulation. There are two coloured lines. The purple line records levels of poor self-regulation in general- outside school if you like. As you can see, when the first 2020 lockdown was first imposed, there was little impact on young people’s self-regulation in general. Poor self-regulation only increased in the third lockdown in January 2021, when schools were closed again 12 months ago.

The orange line records levels of poor self-regulation when in school. It’s useful to think of school as a kind of distinct road- a road with signposts, activities, lessons, traffic, policies, destinations and supervision and so on. Therefore it is not surprising that young people self-regulate differently ON the school road compared to when they are OFF it.

“At its peak during the third lockdown 12 months ago, in-school self-regulation was 40% worse than before the pandemic.”

As you can see, poor self-regulation increased sharply in March 2020 on the school road- when schools first went online. It recovered a little in the Autumn term when schools reopened, before dramatically increasing again in the third school lockdown in January 2021. At its peak during the third lockdown 12 months ago, in-school self-regulation was 40% worse than before the pandemic.

What we can learn from this

There are three main lessons to take from this data. First, and most obviously, closing schools seriously dysregulates young people. Teacher’s efforts to spin to virtual lessons mitigated much lost learning, but could not compensate for the loss of the wider social and institutional protective factors that being present in, surrounded by and taught in the school environment. The government is right to prioritise keeping schools open and must hope as little virtual teaching is required as possible.

Second, recovering from school lockdowns is taking a long time. It’s now nearly two years since that first March 2020 lockdown- and despite having had open schools for the past nine months, student dysregulation in school remains stubbornly high. In December, our latest data suggested it was still 25% higher than pre-pandemic (with girls at higher risk than boys).

Why is this? It seems some significant, sustained changes to student’s ability to self-regulate in school has been inflicted by the pandemic. I will write more about this in subsequent pieces, but the data suggests this is around the ability to trust others- to trust peers, but more widely to trust teachers and the institution per se.

An erosion of trust- triggered by unpredictable and changing goals (public exams), routines (weekly rhythms blown apart) and pastoral care (which of my teachers really sees me behind a Teams call?) has significantly damaged the critical protective factor for young people of being able to trust others. As a result, as we shall see in my next article, there has been a significant rise in young people looking inwards to protect themselves.

Third, it is likely, but not certain, that even minor measures which reduce students’ predictable routines, reduce their face to face interactions or create a barrier between them and teachers, will have a further negative impact on self-regulation. The controls in a students’ self-regulatory car are, if you like, now sensitised and prone to veering.

“On this evidence, even minor disruptions such as face masks and Covid isolation periods disrupting teaching and learning, will be negatively impactful.”

On this evidence, even minor disruptions such as face masks and Covid isolation periods disrupting teaching and learning, will be negatively impactful. Neither can be it assumed that once these are removed, young people will quickly restore their levels of self-regulatory power. These effects may be with us as a society for many years; we may be creating a new psychological normal. Great care should therefore be taken at even the little interventions put in place for however long.

Self-Regulation is a strong indicator of both present adolescent wellbeing and future social costs

Finally, a note on why the data on self-regulation matters. Over the past 30 years, self-regulation has emerged as one of the strongest, most well established foundations for emotional health, social competencies and academic performance. It is cited as high value for learning by the EEF and the recent OECD 2021 survey of social emotional skills cites self-regulation as a critical factor in educational development. STEER’s own work on self-regulation can be read about HERE.

Strengthening young people’s ability to self-regulate is one of the most strategic investments a society can make in it’s future mental health. Conversely, weakening it is likely to lead to serious tail-costs as poor adolescent self-regulation hardens into long-term adult mental health concerns.

Identify and improve the self-regulation of all your students at risk using STEER Tracking

STEER’s next data collection round will be in February and March. Between now and then we will publish further insights into what our data has told us about the relative risks to boys v girls and how schools can most effectively support them through the months ahead.